“You have mystery service ahead, and will soon enough realize what is expected of you.” Hilma af Klint’s last journal entry

Heather Gentleman’s latest body of work reexamines the stories of five women forever linked by brutality—the victims of Jack the Ripper. Rather than centring the man who took their lives, this exhibition seeks to restore their humanity, elevating them beyond the gruesome notoriety that has overshadowed their identities for more than a century.

Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly were more than just victims; they were daughters, mothers, workers, and dreamers. Yet, history has reduced them to nothing more than the manner of their deaths—sensationalized, dehumanized, and stripped of dignity. Gentleman’s work reimagines their depictions, presenting them not as crime scene images but as women who once lived, loved, and struggled.

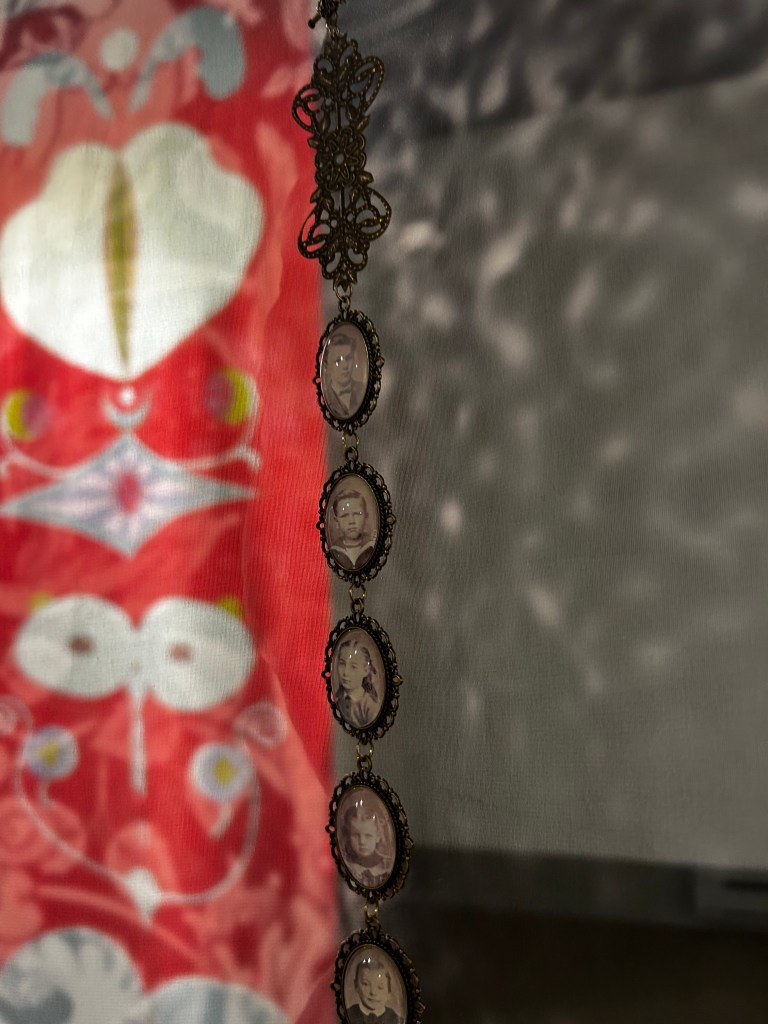

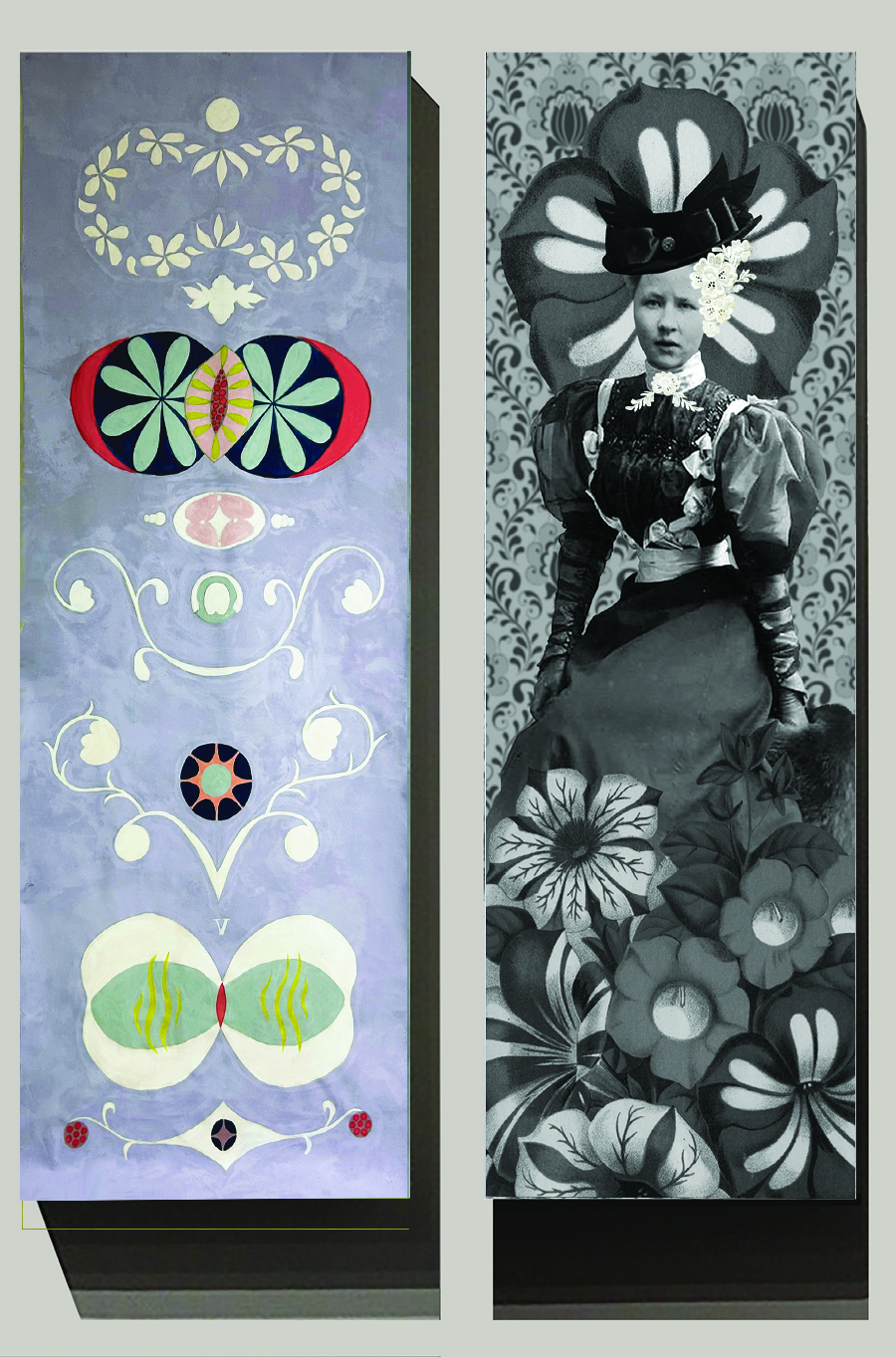

The installation includes suspended panels and reliquaries, forming an immersive space, creating a dynamic interaction between the works and the narrative they represent. Acrylic paintings on raw canvas depict stylized biomorphic forms, reclaiming and reconfiguring their brutalized bodies in a decorative yet symbolic way. The chiffon panels, adorned with hand-sewn lace, reference their labour—sewing for survival in hopes of affording a bed for the night. These translucent collaged prints merge archival photographs with Victorian postcards, presenting the women in resplendent beauty, dressed in finery and surrounded by abundant flowers—perhaps a vision of who they might have been in another life. Reliquaries, filled with memories of comfort, security, and belonging, are anchored by keys, dangling just beyond reach, much like the elusive quest for home and safety.

The ethereal layering of these ghostly chiffon images with the bold biomorphic forms of the acrylic paintings creates a third space—one that is both spiritual and deeply personal. The latter is inspired in part by Hilma af Klint, a Victorian-era artist and spiritualist, and her collective known as The Five, who sought to communicate with spirits through art. In this way, Gentleman’s installation offers a fitting dialogue between history, remembrance, and transcendence. Through this evocative reimagining, The Five are given presence, dignity, and the respect they deserve.

HILMA AF KLINT (October 1862 – 1944)

Throughout her life, Hilma af Klint sought to understand the mysteries she encountered through her work. She filled more than 150 notebooks with her thoughts and studies, delving into spiritual and artistic exploration. Hilma af Klint was a Swedish artist and mystic whose paintings are considered among the first major abstract works in Western art history. A significant portion of her work predates the first purely abstract compositions by Kandinsky. She was part of a group called The Five (De Fem), a circle of women inspired by Theosophy who believed in contacting the High Masters—spiritual entities they communicated with through séances, automatic writing, and drawings. Her paintings, often resembling diagrams, served as visual representations of complex spiritual ideas.

In 1880, following the death of her younger sister Hermina, af Klint’s spiritual interests deepened. Her fascination with abstraction and symbolism was closely tied to the spiritualist movement, which was widely popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. She was particularly drawn to Theosophy, a philosophy blending mystical traditions from various cultures. Theosophy posits that all religions share a common, ancient truth, and that enlightenment can be reached through direct spiritual knowledge rather than dogma. Central themes include reincarnation, karma, the existence of spiritual hierarchies (such as ascended masters), and the evolution of the soul.

In 1908, she met Rudolf Steiner, the founder of the Anthroposophical Society, during his visit to Stockholm. Steiner, who believed that humans were once pure spirits but had become separated from the spiritual world by material existence, introduced af Klint to his ideas on art and spirituality. His teachings later influenced her work.

At the Academy of Fine Arts, af Klint met Anna Cassel, the first of four women who would join her in The Five (De Fem), a group that explored spiritualism through art. The other members—Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman, and Mathilda Nilsson—initially connected as part of the Edelweiss Society, which blended Theosophical teachings with spiritualist practices. The Five regularly held séances, beginning with prayers, meditation, Christian sermons, and readings from the New Testament. They recorded their experiences in a book, documenting messages from higher spiritual beings they called the High Masters

Through her work with The Five, af Klint experimented with automatic drawing as early as 1896. This exploration led her to develop an innovative geometric visual language that sought to depict unseen forces of both the inner and outer worlds. She studied world religions, atomic structures, and the plant kingdom, extensively documenting her discoveries. She believed that the High Masters used her as a conduit for their messages, and she translated these revelations into symbolic metaphors within her paintings.

She often felt as though an external force guided her hand, writing in her notebooks: “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brushstroke.”

Af Klint meticulously numbered her paintings, organizing them into series that explored spiritual themes, life stages, and metaphysical concepts. Each painting’s position within a series held symbolic significance. The acrylic panels numbered 1 to 5 reference the members of both The Five spiritualist group and the Five Whitechapel Women. These panels are derivative of af Klint’s work, including her botanical images and painting around the form and allowing the brushstrokes to be visible. She saw plants as spiritual beings, exploring their vegetal souls and using their structures as pathways to abstraction and spiritual understanding. The figures in these works are deconstructed and reassembled in a visually striking and decorative manner, symbolizing the souls of Catherine, Polly, Mary Jane, Annie, and Elizabeth. These biomorphic forms act as a gateway, allowing The Five to emerge and share their stories.

POLLY (MARY ANN) NICHOLS (1845 – August 31, 1888)

Polly Nichols was born the second of three children born to Edward Walker, a blacksmith, and Caroline, a laundress in a small flat in one of the many streets in the proximity of Fleet Street. Fleet Street and its surrounding lanes buzzed with life, serving as the heart of printing. This vibrant area was home to authors, printers, newspaper men, and booksellers. In the maze of narrow alleyways, densely packed homes echoed with the cacophony of lively discussions and the relentless clatter of printing presses. For Polly, this meant that her family of five lived in a single, cramped 8 x 8-foot room, where one bed was shared by the entire household. Interestingly, her father became a creator of type, a trade that paid better than blacksmithing. Moreover, the proximity to the literary world meant that families involved in the printing trade were often encouraged to attend national schools. Polly attended school until the age of 15 and learned to read and write—an accomplishment that was somewhat rare for girls of her social class at the time. However, her childhood was marked by tragedy when her mother died of tuberculosis when her younger sibling was just 3 years old. He also passed away 18 months later, further deepening the family’s sorrow.

With her mother gone, Polly stepped up to take on the role of caretaker for her father and older brother. The loss of her mother and the difficult conditions in which her family lived set the stage for the challenges Polly would face as an adult. At age 18, Walker married a printer’s machinist named William Nichols. Following their marriage, the couple briefly on their own before residing with Polly’s father and brother. Over the next 13 years, the couple had five children: Edward John, Percy George, Alice Esther, Eliza Sarah, and Henry Alfred. The extra mouths to feed, caused the couple to look for a home of their own.

In 1880, Polly and William moved into their own three-room home at 6 D-Block, Peabody Buildings, Stamford Street, Blackfriars Road, paying a weekly rent of 5s. 9d. Next door lived Rosetta Wools, whose husband was working abroad as a ship’s cook. Since Polly’s needed help to take care of her brood, Rosetta was hired to help. The adjoining doors and shared water closet fostered an unusual closeness between the two households, and over time, a relationship developed between Rosetta and William. Living in a cramped space where seven people shared three small rooms only amplified the financial pressures on the family, and the strain of the extra relationship soon became apparent. It seems likely that William was hoping the situation would push Polly to leave. Eventually, the escalating tensions led to physical altercations, with Polly often on the receiving end of William’s anger—a period that may also have marked the beginning of her drinking.

Polly tried to escape her troubled home life several times, leaving to live with her father and brother on five separate occasions, only to be urged by her family to return each time. Ultimately,, she left for good, entrusting the care of her children to William. It did not take long for he and Rosetta to move out and relocate. Just a year after leaving, Rosetta gave birth to a son and took on the role of mother to Polly’s children.

By 1881, Nichols was residing at the Lambeth Workhouse, where she identified herself as a charwoman. The conditions were harsh— Workhouses were intended to be unpleasant places, aiming to discourage people from relying on public assistance by making the conditions worse than life outside. They were often severely overcrowded, with multiple people sharing beds and living in cramped quarters. Hygiene was poor, leading to unsanitary conditions and frequent infestations of vermin. The food provided to inmates was meagre and unappetizing, barely enough to sustain them. The diet of bread and skilly (an oatmeal dish flavoured with meat that sometimes even contained rat droppings) were common. They were required to perform monotonous and physically demanding labor, such as breaking stones, crushing bones, or picking oakum. Strict rules governed daily life, and any perceived infractions were met with harsh punishments, including beatings and confinement and the risk of sexual assault from overseers. She left that same year.

Her whereabouts for much of the following year remain unknown, until she returned to the Lambeth Workhouse in 1882. In 1883, records show she lived with her father in Walworth for several months, but a quarrel eventually forced her to leave his home. At the time, societal norms were unforgiving: a woman who left her husband was deemed immoral for forsaking her children and spouse, condemning her to a life of poverty. With wages from domestic service, sewing, and laundry work barely sufficient to survive, most women had little choice but to return to the workhouse or live with a man.

Legally obligated to support his estranged wife, William Nichols initially provided a weekly allowance of five shillings. However, in the spring of 1882, upon learning that she was living with another man, he halted these payments. In response, Nichols issued summons through the Lambeth Union, demanding the continuation of his allowance. When parish authorities attempted to collect the maintenance money, William explained that his wife had abandoned her family—leaving their children in his care—and was now living with another man, allegedly earning money through prostitution. Since the law did not require him to support a wife who was making money through illicit means, Nichols ultimately ceased receiving any maintenance payments. This was a double standard as William was free to live common law with another woman, but Polly was considered immoral for doing the same.

Nichols spent the remainder of her years moving between workhouses and boarding houses, surviving on charitable handouts, sewing, and charring—even though she often squandered her earnings on alcohol. In 1887, she entered into a relationship with Thomas Stuart Drew, a widower and father of three, but the couple separated. By December that same year, Nichols was forced to sleep rough in Trafalgar Square until a clearance pushed her back into the Lambeth Workhouse, where she stayed for less than two weeks.

In 1888, the matron of Lambeth Workhouse, helped Nichols secure a position as a domestic servant for an older couple in Wandsworth. Shortly after starting the job, Nichols wrote a letter to her father expressing her general satisfaction with her new role. However, due to her struggles with alcoholism and the fact that her employers were teetotallers, she left the position after just three months. During her abrupt departure, Nichols stole clothing valued at £3 10s and fled the premises.

During the summer of 1888, Nichols resided in a common lodging-house in Spitalfields, sharing a bed with an elderly woman named Emily “Nelly” Holland. She then relocated to another lodging-house in Whitechapel.

At approximately 11:00 p.m. on 30 August, Nichols was seen walking along Whitechapel Road. Shortly thereafter, she visited the Frying Pan public house on Brick Lane in Spitalfields, leaving at 12:30 a.m. By 1:20 a.m., she had returned to the kitchen area of her Flower and Dean Street lodging-house. About fifty minutes later, the deputy lodging-house keeper encountered her and requested the 4d fee required for her bed. Nichols replied that she did not have the money, and she was ordered to leave. Unperturbed, she gestured toward her new black velvet bonnet and remarked, “I’ll soon get my doss money. See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.” It appears she intended to sell the bonnet to earn enough for a bed, although this statement was used as a “confirmation” that she was out to prostitute herself.

Nichols was last seen alive by around 2:30 a.m. on Osborn Street, roughly one hour before her death. Holland noted that Nichols appeared extremely intoxicated, even slumping against the wall of a grocer’s shop. When Holland tried to persuade her to return to the Thrawl Street lodging-house, Nichols dismissed the suggestion, stating, “I have had my lodging money three times today, and I have spent it.” Convinced that Nichols was unconcerned about earning the additional 4d needed for her bed, Holland eventually parted ways with her as Nichols continued her walk toward Whitechapel Road.

ANNIE CHAPMAN (1840 – 1888)

Annie Chapman was born the eldest of five children born to George Smith and Ruth Chapman. Her early years were influenced by her father’s military career and the family’s movements between London and Windsor. After the birth of their second child, the family moved to Knightsbridge, where George transitioned into work as a valet, and eventually, they relocated to Berkshire.

Annie’s proclivity for alcohol emerged at a young age. According to her brother Fountain, she “first took a drink when she was quite young” and quickly developed a weakness for it. Despite the repeated pleas from her siblings—who even persuaded her to sign a pledge to abstain—she succumbed to temptation. By 1861, census records show that while the rest of the Smith family had moved to the parish of Clewer, Annie remained in London, likely to fulfill her duties as a domestic servant. During this period, her father, served as the valet to a Captain. Tragically, after spending an evening with his employer in a pub, he took his own life by cutting his throat. Her mother received money from the Captain, who also covered the funeral expenses. With that financial support, she purchased a home and converted it into a boarding house, using the rental income to sustain her family.

In 1869, Annie married John James Chapman—a boarding house tenant of no relation—in a ceremony in Knightsbridge, witnessed by her sister Emily Laticia and a colleague of John’s. Over the following years, the Chapmans moved among various West London addresses. In the early 1870s, John Chapman secured employment serving a nobleman on Bond Street.

The couple faced immense personal tragedy. They had seven children, but only three survived infancy. Their children included Emily Ruth (who died at age 12), Ellen Georgina (who died just one day old), Annie Georgina, Georgina (who died at 9 weeks), George William Harry (who died at 11 weeks), Mariam Lilly (who died at 10 weeks), and John Alfred, who was born with a disability. The family sought medical help for John Alfred at a London hospital before ultimately placing him in an institution for the physically disabled near Windsor.

Though Annie had managed to wean herself off alcohol by 1880, her son’s disability eventually led to a gradual relapse. In 1881, the Chapmans left West London for Windsor, where John Chapman took a job as a coachman. The family lived in the attic rooms of a Cottage, but their fragile stability was shattered when, a year later, their daughter Emily Ruth died of meningitis on her brother’s second birthday. In the wake of this loss, both Annie and her husband turned to heavy drinking. Over the ensuing years, she was repeatedly arrested for public intoxication, though records do not indicate that she ever faced court proceedings. By 1884, the strain had driven Annie and John Chapman to separate by mutual consent. John was given an ultimatum from his employer – separate from his wife or lose his job. Custody of their surviving daughter remained with John, while Annie returned to London, supported by a weekly allowance of 10 shillings sent via Post Office Order.

After separating from her husband, Annie Chapman resettled in Whitechapel, subsisting mainly on the weekly allowance. Over time, she moved between common lodging houses in Whitechapel and Spitalfields. By 1886, she was living with a wire-sieve maker—a circumstance that earned her the nicknames “Annie Sievey” or “Siffey” among acquaintances.

Two years later, in John Chapman resigned from his job due to declining health and moved to New Windsor. He died on Christmas day from liver cirrhosis and edema, halting the weekly payments. Annie learned of his death from her brother-in-law, and her surviving daughter, then 13-year-old Annie Georgina, was either placed in a French institution or joined a travelling circus troupe, according to differing accounts. Soon after, the sieve-maker left her, possibly due to the loss of her support, and moved to Notting Hill. One friend later recalled that Annie had become depressed and seemed to lose her will to live.

By May or June 1888, Annie had taken up residence at Crossingham’s Lodging House, paying 8d a night for a double bed. She supplemented her income through crochet work and selling flowers. A bricklayer, named Edward Stanley, would often stay with her from Saturday to Monday, occasionally covering her bed fee.

On 7 September, Amelia Palmer encountered Annie on Dorset Street. Palmer later told police that Annie appeared visibly pale, having just been discharged from the casual ward of the Whitechapel Infirmary, and complained that she felt “too ill to do anything.” Shortly after midnight on, Annie was short of the 4 pence needed for her nightly lodging fee. At around 12:10 a.m., she drank a pint of beer in the kitchen with fellow lodger, and then told another resident that she had visited her sister in Vauxhall and received 5 pence from her family. A tenant observed her take a box of pills from her pocket, which broke; Annie then wrapped the pills in an envelope torn from a mantlepiece before leaving. At approximately 1:35 a.m., she returned with a baked potato, ate it, and left once more—apparently hoping to find a friend who could lend her the fee, as she remarked, “I won’t be long, Brummie. See that Tim keeps the bed for me.” Evans later saw her walking in the direction of Spitalfields Market. After her death, the coroner noted that Annie’s lungs and brain membranes were in an advanced state of TB—conditions that would have claimed her life within months regardless of her lifestyle.

ELIZABETH STRIDE (1843 – 1888)

Elizabeth Stride was born Elisabeth Gustafsdotter in Stora Tumlehed, a rural village in Torslanda Parish, west of Gothenburg, Sweden. She was the second of four children born to farmer Gustaf Ericsson and his wife, Beata Carlsdotter. Raised in the Lutheran faith, Elizabeth spent her childhood performing chores on the family farm.

At 15, she was confirmed at the Church of Torslanda, with records noting her thorough biblical knowledge. The following year, she left her rural home for Gothenburg in search of employment, soon finding work as a domestic servant for a couple named Olofsson. She later moved to another district of the city, continuing to work in domestic service.

At some point during her employment, Elizabeth became pregnant. It is unclear whether the relationship was consensual, as young, naïve farm girls were often vulnerable to exploitation by their employers or those within their social circles. She briefly lived with the child’s father, taking his name for propriety’s sake. However, when he abandoned her, she was left in a desperate situation.

At six months pregnant, Elizabeth was arrested for prostitution—a charge that often included unwed pregnant women, women seen alone at night, or those in the company of unrelated men. She was subjected to mandatory medical examinations for venereal disease, a humiliating process in which women were forced to undress and wait in the cold courtyard of the police hospital under the guise of uniformed officers. She was diagnosed with syphilis and endured painful treatments, including iodine ingestion and the surgical removal of sores. The stress and illness caused her to go into preterm labor, and she gave birth to a stillborn girl.

Upon her release, Elizabeth had no family support or job prospects outside of sex work. Once registered as a prostitute by the police, finding other employment became nearly impossible. She was forced to rent small attic rooms to continue working in the only profession left available to her.

In 1866, Elizabeth left Sweden for London. The exact reason for her move is unclear. She told some people that she had been employed in domestic service for a “gentleman” near Hyde Park, while others heard that she had traveled to visit relatives and decided to stay. It is likely that she funded the trip with the 65 kronor she inherited after her mother’s death in 1864.

After arriving in London, Elizabeth learned both English and Yiddish in addition to her native Swedish. In the late 1860s, she briefly dated a policeman.

In 1869, she married John Thomas Stride, a ship’s carpenter from Sheerness who was 22 years her senior. For several years, the Strides lived on East India Dock Road and ran a coffee shop. Elizabeth left her comfortable position in service and worked cooking and cleaning at her own business. Coffeehouses played a crucial role in society, much like they had in previous centuries. They provided a respectable alternative to pubs, catering especially to middle-class professionals, writers, and businessmen who sought a place to read, discuss politics, and engage in intellectual debates. Many coffeehouses also served affordable meals, making them particularly appealing to working men who lived in rented rooms without kitchen facilities. The warm atmosphere, often with a fire burning in the colder months, created a welcoming space for relaxation after a long day. The first location proved to be unsuccessful and they moved locations. John had hoped that he would receive a substantial inheritance as his ailing father was a rich landlord with many properties and John had stayed close to him as a dutiful son. With this in mind, he invested in a new located going into debt to do so. Unfortunately, his father’s will did not include him and all the properties were divided up among his siblings, some of whom By 1874, however, their marriage had begun to deteriorate, possibly with the economic struggles and the inability to produce children. Elizabeth’s syphilis, which would have progressed to a latter stage could have made her infertile. It is highly unlikely she shared this information with her husband. The following year, financial struggles likely forced John and Elizabeth to sell the coffee shop.

By 1877, Elizabeth had been admitted to the Poplar Workhouse, indicating that the couple had separated. However, census records from 1881 suggest they briefly reunited and lived in Bow. By the end of that year, though, they had separated permanently. In 1881, John was admitted to a Whitechapel infirmary with bronchitis. He was a month later , and Elizabeth soon moved into one of the common lodging houses on Flower and Dean Street, a notorious slum in Whitechapel. In 1884, John Stride died of tuberculosis.

After her husband’s death, Elizabeth often told people that she and John had worked on the steamer Princess Alice and that he, along with two of their nine children, had drowned when the vessel sank in 1878. According to her, she had survived by climbing the ship’s mast but had been kicked in the mouth by another survivor, resulting in a permanent stutter. However, no records support these claims, and it is likely she fabricated the story to elicit sympathy. It was common at that time to receive support for being a victim of such a tragic accident.

During her years in common lodging houses, Elizabeth sometimes received assistance from the Church of Sweden in London. She also received weekly funds and, occasionally, clothing, from a woman who mistook her for her long lost sister.

From 1885 until her death, she was in an on-again, off-again relationship with Michael Kidney, a dock labourer. Their relationship was tumultuous, marked by frequent separations. In 1887, Elizabeth filed an assault charge against Kidney, though she later failed to appear in court, and the case was dismissed.

Elizabeth earned a meagre living through sewing and housecleaning. An acquaintance described her as having a generally calm temperament, though she appeared in Thames Magistrates’ Court about eight times for being drunk and disorderly or using obscene language.

The evening before her murder, September 29, she cleaned two rooms at her lodging house and was paid sixpence. She borrowed a brush from a fellow lodger to tidy up her appearance. At 6:30 p.m., she visited the Queen’s Head pub with a friend.

Throughout the evening, Elizabeth was seen by multiple witnesses. At 11:00 p.m., she was spotted with a short man in a morning suit and bowler hat. Forty-five minutes later, she was seen standing with a man in a peaked cap and black coat. The two were kissing, and the man remarked, “You would say anything but your prayers.”

At 12:35 a.m., another witness saw Elizabeth with a man wearing a hard felt hat standing across from the International Working Men’s Educational Club, a socialist and Jewish social club. The man carried a package about 18 inches long. Having no reason for suspicion, Smith continued his patrol.

Between 12:35 and 12:45 a.m., dockworker James Brown saw a woman he believed to be Elizabeth leaning against a wall on the corner of Berner Street. She was speaking with a man in a long black coat. Brown overheard her say, “No. Not tonight. Some other night.”

At some point after this encounter, Elizabeth Stride was murdered.

CATHERINE EDDOWES (1842 – 1888)

Catherine Eddowes was born the sixth of twelve children born to tinplate worker George Eddowes and his wife, Catherine (née Evans), who worked as a cook at the Peacock Hotel. By 1857, both of Catherine’s parents had passed away, leaving her and three of her siblings orphaned. The four were admitted to a Bermondsey workhouse and later attended a local industrial school, which aimed to teach them a trade. One of Catherine’s older sisters, Emma, and an aunt helped her secure employment as a tinplate stamper in Wolverhampton. She moved there to live with her aunt while continuing her education at a charity school.

Within months of starting work, Catherine was dismissed for theft. This led to tensions with her aunt, and she soon left Wolverhampton for Birmingham, where she briefly stayed with her uncle, Thomas Eddowes, a shoemaker. She found employment as a tray polisher but left after about four months to return to Wolverhampton, where her grandfather arranged another tinplate stamping job for her. Nine months later, she moved back to Birmingham.

Catharine had been cast out by her aunt for falling for an Irish ex-guardsman, Thomas Conway, a former soldier in the who received a small regimental pension who eked out a meagre living by hawking penny ballads near the town’s public houses. Young, headstrong, and utterly enamoured with the handsome, poetic Irishman—who went by the name Thomas Conway-Quinn—she followed him to Birmingham. Her striking looks and vivacious spirit became valuable assets as she helped him peddle his rhyme sheets along the streets and in the pubs.

No records confirm that they ever married, though Catherine began referring to herself as “Kate Conway” and even had Conway’s initials tattooed on her left forearm. The couple had two children—Catherine Ann and Thomas Lawrence—and supported themselves with occasional labouring work when Conway’s health allowed.

Whenever an execution took place, the pair would venture to Warwick, Worcester, or Stafford, making a tidy profit as the assembled crowds eagerly paid a penny for a rhyming memento of the event. On one such journey to Stafford in January 1866, Catharine she witnessed the hanging of her own cousin, Christopher Robinson—executed in Wolverhampton for murdering his partner. She embraced the opportunity selling scaffold ballads about him to a crowd estimated at around 4,000 people that morning.

They returned from Stafford in fine style, having secured inside seats on Ward’s coach with the proceeds from their ballad sales. The trip had been exceptionally lucrative. They ordered an additional 400 copies from a printer on Church Street. As a token of his gratitude, he rewarded Catherine with a flowered hat.

In 1868, Catherine and Conway moved to London, taking lodgings in Westminster. Their third child, a second son, was born in 1873. Over time, Catherine developed a drinking problem, which caused increasing conflict within the family. According to their daughter, they began living on “bad terms” due to her mother’s drinking, which worsened throughout the 1870s. By the late 1870s, their fights had turned violent, and Catherine was occasionally seen with black eyes and bruises.

By 1880, Catherine and Conway were living in Chelsea, with their two youngest children (their eldest had already left home). That same year, Catherine left Conway.

The reason for Catherine’s move from Chelsea to London’s East End is unknown, but by 1881, she was living with John Kelly, a fruit salesman, at Cooney’s common lodging house in Spitalfields—a notorious criminal area. She became known to acquaintances as “Kate Kelly.” The lodging house deputy later stated that Catherine seldom drank to excess. However, records show that she was charged with being drunk and disorderly and brought before Thames Magistrates’ Court, though she was discharged without a fine.

While living in Spitalfields, Catherine mostly earned money doing domestic work, such as cleaning and sewing for the Jewish community in nearby Brick Lane. By the mid-1880s, she and Kelly supplemented their income with seasonal hop-picking work in Kent each summer.

When Catherine couldn’t afford a bed in a lodging house, she often tried borrowing money from her sisters or her daughter. She frequently sought help from her older sister who lived in Greenwich. If unsuccessful, she was known to sleep rough in the front room of 26 Dorset Street, known locally as “the shed.”

That September, Catherine and Kelly traveled to Kent, for their annual hop-picking work. On the way, Catherine purchased a jacket from a pawnshop, while Kelly bought a pair of boots in Maidstone. During the harvest, they befriended a couple, sharing a barn for shelter.

Catherine and Kelly walked the 61 km back to London and spent the night at the Shoe Lane casual ward in the City of London. The following night, they stayed in separate lodging houses.

By the next day, the couple had spent nearly all their earnings. At 8:00 a.m., they met at Cooney’s lodging house for breakfast, using their last few pennies to buy tea and sugar. They agreed to split their remaining sixpence: Kelly kept fourpence to secure a bed, while Catherine took twopence, enough for a night at Mile End Casual Ward.

That afternoon, Catherine told Kelly she was going to Bermondsey to borrow money from her daughter, who had been married to a gun-maker in Southwark for three years. They parted ways in Houndsditch at around 2:00 p.m., and Catherine promised to return by 4:00 p.m. However, Kelly used money from pawning his boots to secure a bed for the night and, according to the lodging-house deputy, did not leave.

At 8:30 p.m., a police officer found Catherine drunk and lying on the pavement and was taken to the station to sober up. When asked for her name, she responded with “Nothing.” Within 20 minutes, she had fallen asleep in a cell.

At 12:30 a.m. on September 30, Catherine asked the officer when she could leave. He told her, “When you are capable of taking care of yourself.” Thirty minutes later, at 1:00 a.m., she was deemed sober enough for release. As he escorted her outside, she cheerfully said, “All right. Good night, old cock.” Instead of turning right toward her lodging house on Flower and Dean Street, Catherine turned left toward Aldgate.

At 1:35 a.m., three men—Joseph Lawende, Joseph Hyam Levy, and Harry Harris—saw Catherine standing at the entrance of Church Passage, near Mitre Square. She was speaking to a man of medium build with a fair moustache. According to Lawende, she was facing the man with one hand on his chest but did not appear to be resisting him. This was the last sighting of her alive.

MARY JANE KELLY (1863 – 1888)

Mary Kelly’s origins are shrouded in mystery, with little documented evidence to confirm her early life details. Much of what is known about her comes from accounts that may have been embellished or even fabricated. According to Joseph Barnett, the man she lived with before her murder, Kelly claimed she was born into a family of 11 in Limerick, Ireland to John Kelly and his wife who worked as a Forman as an ironworks factory. It is unclear whether she referred to the city or the county. As a child, her family reportedly moved to Wales. Her landlord, John McCarthy, recalled that she occasionally received letters from Ireland.

Kelly told acquaintances that her parents had disowned her, although she remained close to her sister. She described her family as moderately wealthy, a claim supported by both Barnett and her former landlady, who referred to Kelly’s background as “well-to-do.”. She reportedly had seven brothers and at least one sister, with one brother, Henry, said to have served in the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards. Kelly once mentioned to a friend that a female family member worked in the London theatre scene. Carthy described Kelly as “an excellent scholar and an artist of no mean degree.” It was common for the middle class to ensure their children received a proper education to establish an air of respectability. A quality education was evident not only in one’s ability to read and write, but in one’s comportment, erudition and interests. Her artistic ability was more likely developed in fashionable young ladies schools. She was always neatly dressed and had no regional accent possibly as a result as elocution lessons.

There were a variety of stories that was cobbled together, changing depending who she spoke to. She told others she had a child born in 1882. After her death, inquiries were made in Wales and Ireland to find relatives with no avail. No brother in the scotch guard, no friend or family from the past, no Kellys or Davis’ match up in census in either country matched.

At around 16 years old, Kelly reportedly married a coal miner named Davis, who died in a mining accident two or three years later. There, however, is no record of this. She may have been living with him as a mistress or common law wife. Left without support, she moved to Cardiff and spent 8 months in an infirmary. This may have been the time she gave birth to the child she mentioned to Barnett, but there is no record of a pregnancy. At the time, Cardiff had two private refuges for fallen women. It was considered that women and girls who engaged in sex outside of marriage suffered from mental illness and were sent to asylums for rehabilitation. Mary mentioned that she stayed in one of these institutions at one time in her life. She then went to live with a cousin, who was working as a prostitute and this was when she started sex work.

By 1882, Kelly had left Cardiff for London, briefly working for a tobacconist in Chelsea before securing employment as a domestic servant in Spitalfields. Through an acquaintance with a French woman she met in Knightsbridge, Kelly found work in a high-class West End brothel, where she became one of its most popular girls. She spent her earnings on fine clothing and hired carriages. Women would meet with wealthy clients who would meet at a private ball with about 80 guests. Each male guest would pay for his female escort, the event space, the band and dinner. Men in top hats and women in ballgowns were common. Organized by a discreet madame, gentlemen and high end escorts would meet at posh restaurants, music halls, theatre, or the races, then end in leave in carriages to private lodgings or hotels. This sojourns could last for days and they would be billed accordingly along with possible purchases of trinkets or new dresses. Mary Jane, a young beautiful woman with her proper elocution and education, in her early 20’s drove about in a carriage and accumulated a number of luxurious dresses. It was at this time, she began to call herself, Marie Jeannette. She was well aware that she was at the top of her career and would take opportunities that presented themselves.

She was reportedly invited to France by a client. She packed her expensive dresses into a trunk which she expected her madame to send to her in Paris. The box was never sent. She may have realized then, she had been deceived and colluded to the man who took her there. She returned to London within two weeks, having disliked the experience. The trafficking of women from the UK to Europe had become quite lucrative. Naive British young women, domestics and sex workers who were sent to through false promises such as proposals for marriage or work opportunities. They were often plied with drugs or drink and given false travel documents. Their clothing would be taken from them and they would be coerced into indentured work to pay back their new clothes, lodging and cost of the commission to bring her there. Women were only allowed to leave during certain hours and to submit to twice weekly examinations for VD. A woman who could not speak the language and was controlled by the madame had little recourse. Mary Kelly’s education included the ability to speak French which allowed her to escape. However, she was now in a dangerous position as she knew some of the criminals who were abducting women and running the brothels in Paris and their counterparts in London. She would need to keep a low profile from that time forth.

By 1885, Kelly had moved to lodgings near the London Docks North Quay, where she briefly lived with Mrs. Boku, where she lived with several prostitutes and continued her work as a sex worker. When a ship arrived at a dock, the women would engage the sailers, who often did not speak English and would accompany him during his time during his shore leave. Many of them spend their time in the many pubs during the evening and their beds during the day. Women were generally careful not to drink much as the danger of the men turning violent was common. She and Boku travelled together to her previous madame in Knightsbridge to retrieve a box of her expensive dresses but the trip was not fruitful. The trip led a man to come looking for her, which frightened Kelly, as she knew the men who had abducted her were dangerous.

she was quiet when sober but rowdy when drunk. She often sang Irish songs but could become quarrelsome, earning her the nickname “Dark Mary which caused her to be turned out of the brothel. She soon moved in with Mrs. Carthy in Breezer’s Hill, Ratcliffe Highway, which was a dangerous area where murders were common. She later had a succession of relationships with men that she lived with.

By 1886, Kelly was residing at Cooley’s Lodging House in Spitalfields.In 1887, she met 28-year-old Joseph Barnett, a fish porter. After a brief courtship, they decided to live together. They moved between various lodgings before settling at 13 Miller’s Court, off Dorset Street, in early 1888. The room was small, poorly furnished, and cost 4 shillings and 6 pence per week. A broken window near the door was used as a makeshift peephole, sometimes covered by a coat.

By 1888, Kelly had grown weary of her lifestyle and expressed a desire to return to Ireland. John McCarthy, her landlord, recalled Barnett lost his job in July 1888, reportedly due to theft. Kelly returned to prostitution, allowing other women in similar circumstances to stay in their room on cold nights. Barnett tolerated this until he and Kelly quarrelled over her sharing the room with a prostitute known as “Julia.” Barnett left Miller’s Court on October 30, a little over a week before Kelly’s murder, and took lodgings at New Street, Bishopsgate. Still, he visited Kelly almost daily, sometimes giving her money.

That night, Kelly was visited by a friend, followed by another, who recalled Kelly warning her, “Whatever you do, don’t you do wrong and turn out as I have.” Kelly was later seen drinking at the Ten Bells pub. At 11:45 p.m., fellow Miller’s Court resident Mary Ann Cox saw her returning home, drunk, with a stout, ginger-haired man in a bowler hat. Kelly bid Cox goodnight, saying, “I am going to have a song,” and was last heard singing “A Violet from Mother’s Grave.” The singing ceased around 1:30 a.m.

An acquaintance, claimed to have seen Kelly at 2 a.m. on November 9. She asked him for sixpence but walked off after he told her he had no money. Hutchinson then saw her approached by a well-dressed man, who gave her a red handkerchief. They walked to Miller’s Court together, and Hutchinson followed them briefly before leaving at 2:45 a.m.

A laundress, reported seeing a man standing outside Miller’s Court at 2:30 a.m. She also saw a drunk woman in the courtyard. At 3 a.m., Mary Ann Cox returned home but heard no sound or light from Kelly’s room. Around 5:45 a.m., she thought she heard someone leaving the residence.

She was found by her landlord the next morning.

EPILOGUE

Hilma af Klint, sought guidance from Rudolf Steiner for her abstract, spiritual paintings. She hoped Steiner would understand and appreciate her work, even envisioning a temple to house her work. He was unimpressed by her approach and advised that her paintings should remain unseen for fifty years. This response devastated af Klint, causing her to stop painting for four years. In her last will and testament, af Klint stipulated that her work should not be exhibited for twenty years after her death.

She was the mother of abstraction and a pioneering spiritual artist who and was deeply engaged in channeling unseen forces, creating work that was largely unrecognized in her time. The Five women murdered by Jack the Ripper, on the other hand, were buried but not truly “laid to rest,” as their identities were overshadowed by the mythos of their killer rather than their own lives.

Hilma af Klint’s art is finally being recognized for its visionary depth, while the stories of the Ripper’s victims are being reclaimed, shifting the focus to the women themselves.

Perhaps we can all relate now to her last entry:

“You have mystery service ahead, and will soon enough realize what is expected of you.”