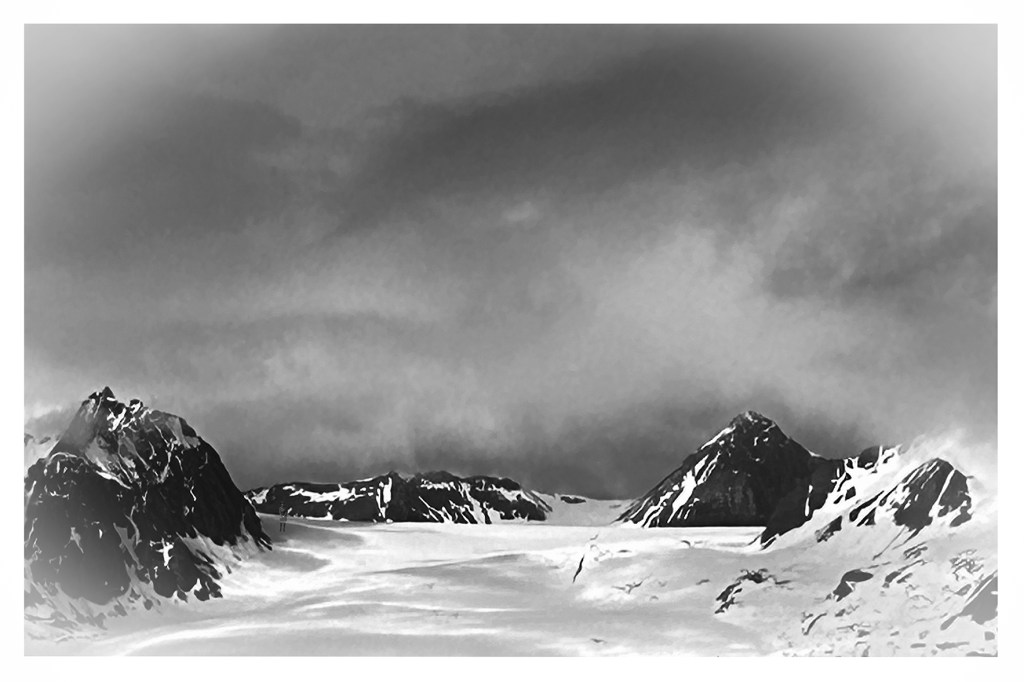

In June 2024, I took part in an Arctic Circle residency in the High Arctic Svalbard Archipelago, traveling aboard a Barquentine tall ship, 1,050 kilometres from the North Pole. For two weeks, I lived among the raw and unsettled edges of the world, where time feels both suspended and immense.

The landscape—severe, shifting, and indifferent—provoked a meditation on memory. In this place where the horizon folds into itself and distinctions blur between solid and liquid, presence and absence, I became attuned to how memory functions—not as a continuous record, but as a series of fragments. We do not carry people or experiences with us in their entirety. What endures are impressions: a glance, a voice, the way someone once moved through a space. Memory, like the Arctic itself, is unstable—mutable, shaped by time and subject to erosion.

On our second landing, we came across the skeletal remains of a reindeer. Its teeth had worn down so severely that feeding had become impossible. It had likely starved—without spectacle, only stillness. Bone, fur, teeth, and silence. Already, its body had begun folding into the terrain. We saw only what was left : the fragments of a once-living body. There was no wholeness, only remains. And in this, I recognized a reflection of memory itself: what we recall are never complete bodies of experience, but scattered pieces. Remnants. Traces. Like bones on the tundra, our memories are what endure, not intact, but weathered, partial, and persistent.

Throughout this residency, I became attuned to the ways memory is entangled with place. We name landscapes to fix meaning to them. Place names become mnemonic vessels, carrying stories across generations. But not every place is named. Some feel silent, unspoken. What happens when there is no one left to carry those stories forward?

As Robert Macfarlane writes, “Stories shape how you see the world… we interpret [landscapes] in light of our own experience and memory.” In this work, I explore the residue of memory—personal, ancestral, ecological—and how we project meaning onto the land in order to situate ourselves within something larger and more enduring.

The Arctic, with its austere beauty and indifference to human drama, became a space where I could contemplate these questions. This project is both elegy and inquiry—an attempt to make sense of how we hold onto the past, how we honour what we’ve lost, and how we find meaning in the fragments that remain. It sits at the intersection of landscape and memory, where personal narrative dissolves into something more collective and elemental.

The mind collects residues: fragments of encounters, distorted impressions, sensations without full context. These are what we use to reconstruct meaning. In this way, memory becomes a creative act, imperfect and interpretive. The people we’ve known and the moments we’ve lived emerge not as wholes, but as silhouettes: ghostlike, partial, sometimes imagined. I began to see the Arctic terrain as a parallel to this condition, its starkness offering space for what is unspoken, unresolved, or obscured.

In my photographic work from this residency, I overlaid ghostlike images of family members onto the Arctic landscape. These apparitions do not haunt the terrain but hover gently within it—elusive flickers of recognition, much like memory itself. Exploring this interplay between figure and place, I became interested in how personal memory embeds itself within landscape, and how the land, in turn, holds what endures in fragments. Extending this exploration, I projected these images onto a 300-year-old whale skull left behind from a whaling encampment. Weathered and monumental, the skull became a surface of time itself, carrying the ephemeral presence of memory in a new, tangible form.

Memory does not arrive all at once, nor does it preserve in full. It reveals itself in fragments—a glance, a voice, the shape of a posture, a place briefly occupied. These pieces do not form a complete picture, but they are how we come to know what has passed. Like the scattered remains of the reindeer, these fragments settle into the terrain of the mind. They are not remnants in the sense of what is missing, but in what gently persists. Memory is impressionistic, assembled from traces, shaped by time, and always partial, yet still meaningful in its incompleteness.